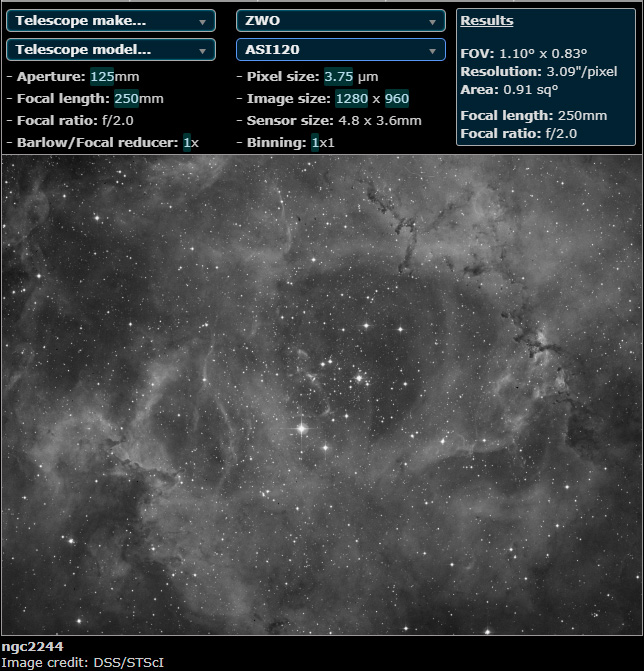

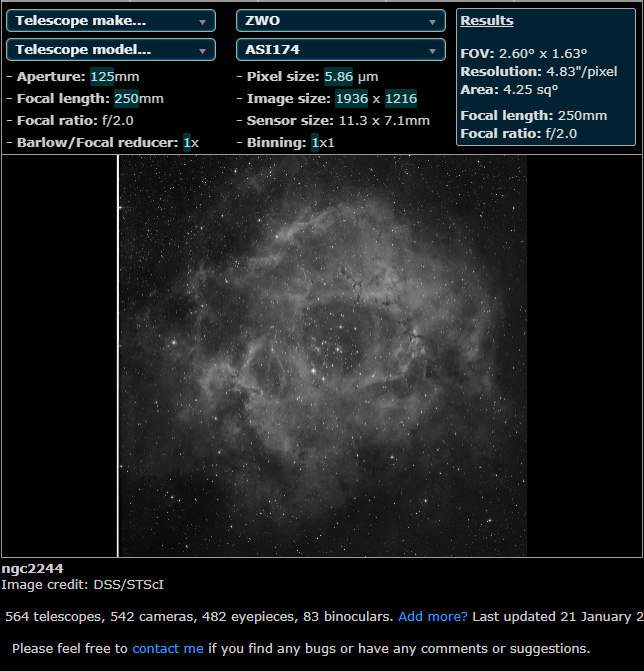

So how big a sensor can you get on the HAC125? Sky-Watcher says the image circle (the usable area at the focus point) is 16mm in diameter. This suggests that the 174 is close to as large as you can go. A good colour camera for the scope would be the QHY 5III585C, with its 12.8mm diagonal.

The IMX533 is a sensor that I’d be keen to see, but I don’t think that sensor appears in any 1.25″ camera. If the telescope becomes popular, it might benefit a canny manufacturer to do that. Just imagine a QHY 5-III-533C.

Focal ratio

One of the most intriguing aspects of this telescope is its focal ratio. F/2 is fast – Formula 1 fast. The curvature on the primary mirror is seriously deep in relation to its diameter and those photons just flood in.

The effect of this is that your exposures won’t need to be long at all. They’ll finish before the noise builds up on the uncooled sensor.

Of course, another benefit of short exposures is that you won’t need to autoguide your mount. This is as long as your polar alignment is good, of course.

There are, however, disadvantages to a super-fast telescope. The critical focal zone (the range in which the focus is good) is very thin, because the light converges quickly. This means that focusing is going to be touchy. We did notice that the thread on the focuser has a fine (0.75mm) pitch, which has gone some way to address this. For the same reason, collimation will be just as touchy, meaning you’ll need a bit of practice.

Conclusion

So what’s the future? Is this the Next Big Thing (albeit very small), and about to replace the Quattro 150 as the new cheap fast imager? Will it mean the end of the expensive cooled camera?

I’m not able to make that judgement without more testing, I’m afraid. I intend to be doing that in the near future. I expect that others on the astronomy field will be interested by this weird little scope.

Another possible outcome is that this telescope is the first iteration. What comes next might be the game-changer.

Price-wise, the HAC125 is not much more than the Quattro 150, which has gathered a reputation as a useful grab-n-go scope, although the Quattro takes a bit of taming. For a similar sized package, which can go on an even smaller mount, the HAC125 might be really fun to muck around with, and a great use for that 174 camera that’s been sitting in a drawer!